Thus spoke Dave

Computer programming came into my life by pure accident. In fact, as a 14-year-old that had just finished primary school, I didn’t plan to have anything to do with computers: I wanted to study agriculture. The actual reason escapes me now; was it because I’d been in the Scouts and wanted to work close to nature? I no longer remember. Anyway, for my next round of education I chose a local secondary, which at that time was a catch-all type of school offering specializations as disparate as Agriculture, Physics, and Information Technology.

I sat the entrance exam and waited for the results, feeling hopeful as I thought I’d done fairly well in the test. After a few weeks I received an official letter saying that I had indeed passed the exam with flying colours. And then it went on to explain, and apologize, that due to low candidate interest there would be no Agriculture class in the upcoming school year – but they’d be very happy to offer me a place in the IT class!

I should have kept the letter because as a joke it was priceless. But my parents thought differently and insisted that I accept the offer, which in the end I did.

You can imagine that in the class I entered in September 1988, I was an oddball right from the start. And not only because I’d made an illogical switch from agriculture to IT. Computers were a rather fancy thing to own in then-Communist Czechoslovakia, a social status thing, so the class was full of children of the local upper crust – doctors, vets, lawyers and company directors. With my working-class background (my dad was a mining machinery mechanic, my mum worked at the railway station), I had little chance to fit in. Luckily, the uncanny forces of social gravity had me seated next to a guy who soon turned out to be an oddball as well. Dave, a shy acne-ridden village teenager who, unlike our pretentious classmates, wanted to study IT simply because he was born a nerd.

In a typical school Dave would have become an obvious target for bullies, but in ours he instead got in the crosshairs of the head teacher. As a die-hard communist bearing an amazing resemblance to Lenin, the head teacher had introduced a school rule not allowing students to wear t-shirts that featured slogans or logos. And I mean any slogans or logos because, you know, what if they were potentially subversive? Now just a few weeks into our first year, Dave was caught in the school corridor wearing a Perestroika t-shirt, a souvenir his father had brought him from the Soviet Union. Facing suspension, Dave defended himself with unexpected grit. He claimed that nothing was wrong with his t-shirt because it promoted the official political doctrine of the Soviet Communist Party. Which in a way it did, so the school board had no other option than to rule in his favour. But he was labelled a dissident, which further cemented his weirdo reputation. (He must have impressed the bullies, though, because they left him alone.)

Through our shared outsider status we inevitably became pals and allies: two friendly ships navigating hostile waters. And soon my life changed beyond recognition! Trying to understand now what was so special about Dave, I see a wonderful contradiction between his reclusive personality and the enthusiasm he beamed with when he was talking about things he loved. More than anybody I knew, he was defined and constantly redefined by his many interests, which included science-fiction, fantasy, cartoons, Dungeons & Dragons, Woody Allen films, Eastern philosophy, rock music, and of course – computers. Not the ones we used at school, horrible and constantly overheating junk! Dave had an Atari 800XE at home, a machine that was in a different league by comparison. A real computer in the technological dry land of Communist Czechoslovakia. Of course we spent hours playing games on it, and just for the record, my favourite was Whomper Stomper, a now-forgotten gem in which you and your trusty aardvark tried to prevent swarms of hungry ants from stealing your picnic lunch. (Why not try the game out on your Amiga using the Atari800 emulator?)

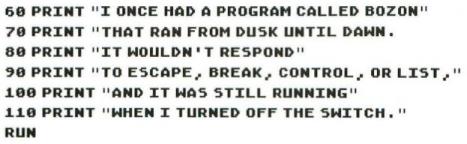

But although the games were great fun, I was more impressed by the fact that Dave was able to program it. I saw that even a pimpled teenager could tell a computer to make sounds, show graphics or move sprites, and I began to feel a desire to learn the witchcraft as well. Agriculture was forever forgotten. I wanted my own computer! I didn’t care if it was an Atari, a Commodore or an Amstrad – I wanted to be able to do things with it. But the programming classes at school were uninspiring, taught by a converted maths teacher who didn’t understand computers, and who rarely seemed to be more than one lesson ahead of his students. Dave instinctively sensed my need for a mentor, and it was him who helped me take my first steps in BASIC and, later, Pascal. I still remember my first ever “program”, which I typed over from Dave’s Atari XE Owner’s Manual:

In case you’re wondering how I could possibly quote a piece of code I last saw 35 years ago, there are two reasons. First, the program actually displayed a poem on the screen, and I find poems easy to remember, especially when they rhyme. Second, the unofficial Czech version of the manual had a mis-translation there: contrary to the English original, it said that the program Bozon continued running after the user turned off the computer switch. Which was a charming nonsense we had a lot of laughs with, so it stuck with me.

The four years with Dave at the secondary school were great and (as I now see) extremely formative, but we parted ways after the school-leaving exam. I took up English studies at the university, and then I went throught a string of teaching and translation jobs, which included a three-year lecturing stint at my alma mater. Dave made a few attempts at studying Economics and then IT, but he always dropped out. We lost touch completely for many years. I heard that he had moved to Prague, where he lived a solitary life and programmed databases for a living. During the three decades we only bumped into each other once. In a typical Dave fashion, my friend refused to go for a pint and instead suggested that we go and see Wallace & Gromit: The Curse of the Were-Rabbit at the cinema. So much for catching up after a long time no see!

Dave had never been to any of our class reunions, so I was stunned to hear that he should be making an appearance at our 30th graduation anniversary earlier this year. In all honesty, I didn’t believe he would show up. I thought I stood a better chance of meeting my classmates who now live in California or Montana than having a chat with Dave. But to everyone’s surprise, he lived up to his word and did come to join us. His many years of social absence lent him a “special guest” status, so he was in high demand throughout the evening. It took a while before I could steal a moment with him and drag him aside so that we could talk in private. After a slightly awkward introductory exchange, during which he confirmed the rumours that he had never married or had kids, I steered the conversation towards what I believed was a safe common ground: computers.

— “Weren’t we lucky that we got a chance to be there when computers were just beginning to be a thing?” I kicked off. Strumming the nostalgia string often makes for an easy way to reconnect.

— “What do you mean?” Apparently, the string didn’t sound right.

— “Er… I mean, wasn’t it great that we had computers in the early days, before everybody and their uncle got a PC?”

— “What exactly was so great about it?”

— “I mean, we were there, right? We were part of it, making it happen. We had to find ways and discover things for ourselves. Learn stuff and all. We did great things others couldn’t. It was exciting to have a computer back then, unlike now.”

— “Was it?” Dave kept replying by asking questions, and I felt that this chat had become unexpectedly difficult to navigate.

— “Don’t you ever miss your little Atari?”

— “Hell no, why would I, for God’s sake? Those old computers were all false starts and dead ends. None of them are relevant any more, so what should I miss about them?”

Thus spoke Dave, and I was dumbfounded. I really didn’t know what to reply, or what else to say next, and so the conversation dwindled away, leaving me with a lot of food for thought (and a few more drinks to finish). Don’t get me wrong: Dave didn’t break any news to me. I’m not a naive simpleton who needed a reality check. But until that evening in late February, I had never questioned that the computers my generation had grown up with were important stepping stones to the technology of today. And now, by a wicked irony of fate, none other than my old partner in crime comes and says such a blasphemous thing!

Believe it or not, I wasn’t able to get over his words for several months. I felt so low that I didn’t touch any of my Amiga projects, including this blog. Overtaken by scepticism, I couldn’t see a point. “Did I just spend thirty years defending something that doesn’t matter?” I asked myself. “Do things become irrelevant when they come out of use? Is there really nothing to be missed about them?”

But as spring progressed towards summer, my usual self began to get the better of me again. And after a while I realized a possibility which, for some reason, I hadn’t considered: that my old mentor was simply wrong. Or that he was being overly pessimistic. Yes, the Amiga and others – including Dave’s Atari – lost the computer race and became a closed chapter, a part of history. But history is something one can hardly call irrelevant. We study history, we reflect on history, we go back to history because it has formed and informed our present. Every closed chapter sets the scene for the chapters we’re reading at the moment. I find the book metaphor quite fitting because in our lives, more often than not we go back a few pages and re-read parts of the story we remember as particulary interesting or inspiring. And sometimes we find that the things we did and the solutions we found were actually quite smart and thrilling, free of the dull complexities that the world imposes on us today. When I use my Amiga, I often feel like the reader in Brian Patten’s poem which starts:

Late at night I sat turning the pages

half-looking at the words I had once read,

astonished at their simplicity.

For me at least, this kind of reading makes a lot of sense!